The U.S. generic drug market didn’t just grow-it exploded. Today, 90% of all prescriptions in America are filled with generic drugs, costing up to 90% less than their brand-name counterparts. But this wasn’t always the case. Before 1984, bringing a generic drug to market meant repeating every clinical trial ever done for the original drug. That meant years of delays and millions in costs. The Hatch-Waxman Act is a 1984 U.S. federal law that created the modern pathway for generic drug approval. Also known as the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, it didn’t just change rules-it rebuilt the entire system for how drugs reach patients.

Before Hatch-Waxman: Why Generic Drugs Were Almost Impossible

In the early 1980s, if you wanted to make a generic version of a drug like ibuprofen or amoxicillin, you had to submit a full New Drug Application (NDA). That meant running your own animal studies, human trials, and safety tests-even though the brand-name version had already been approved by the FDA. The result? Only a handful of generics made it to market. In 1984, just 19% of prescriptions were filled with generics. The cost to develop a single generic drug? Around $2.6 million (in 1984 dollars). That’s over $8 million today, adjusted for inflation. Most small companies couldn’t afford it. Big manufacturers didn’t bother. The market was stuck.

The Hatch-Waxman Breakthrough: No More Repeating Trials

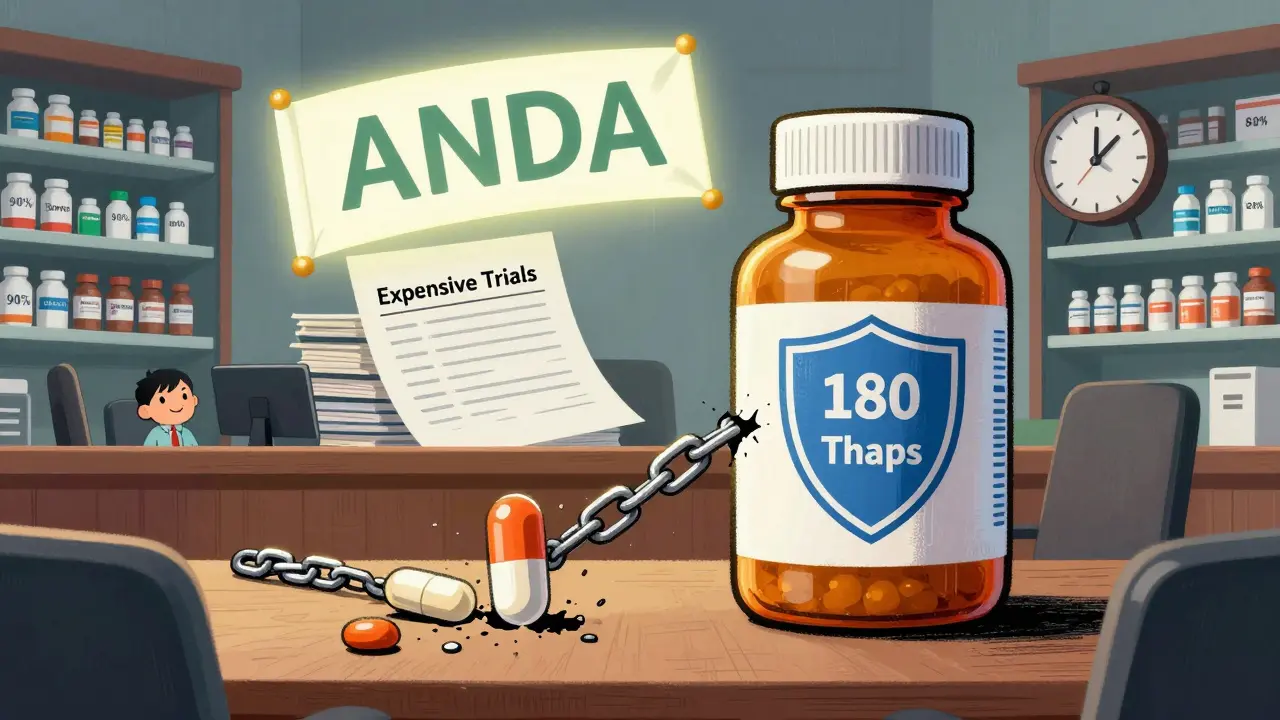

The Hatch-Waxman Act changed everything by creating the Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA. This wasn’t just a shortcut-it was a revolution. Instead of proving safety and effectiveness all over again, generic manufacturers only had to show one thing: their drug is bioequivalent to the brand-name version. That means it delivers the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate. No more repeating clinical trials. No more wasting time and money.

The FDA requires bioequivalence to be proven through pharmacokinetic studies. The generic must match the brand in how fast and how much of the drug enters the blood. The standard? The 90% confidence interval for two key measurements-Cmax (peak concentration) and AUC (total exposure)-must fall between 80% and 125% of the brand’s values. That’s tight. It’s not about looking the same. It’s about working the same.

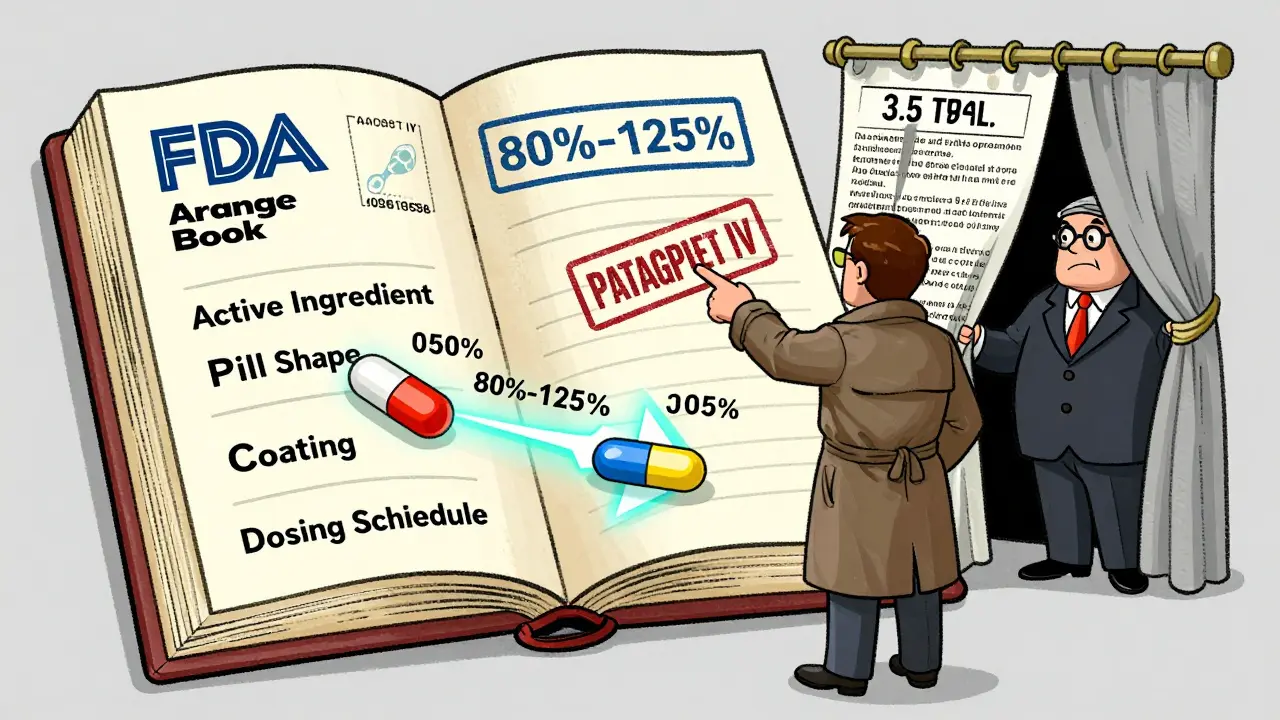

The Orange Book: The Secret Map to Generic Approval

Every brand-name drug has a list of patents. Some cover the active ingredient. Others cover how it’s made, how it’s taken, or even the shape of the pill. The Orange Book-officially called Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations-is the FDA’s public database of these patents. It’s the roadmap for generic companies.

When a generic manufacturer files an ANDA, they must check the Orange Book and then make one of four legal statements, called paragraph certifications:

- Paragraph I: No patents listed.

- Paragraph II: The patents have already expired.

- Paragraph III: We’ll wait until the patent expires before selling our drug.

- Paragraph IV: This patent is invalid, or we won’t be infringing it.

Paragraph IV is the big one. It’s the legal shot across the bow. If a generic company files a Paragraph IV certification, they’re saying, “We’re ready to challenge your patent.” That triggers a legal race.

The 180-Day Exclusivity Prize

Why would a generic company risk a lawsuit? Because the first one to file a Paragraph IV certification gets a reward: 180 days of market exclusivity. During that time, no other generic can enter the market-even if they’ve filed their own ANDA. This is the engine of competition. It turns patent challenges into high-stakes races.

Imagine a drug with $1 billion in annual sales. The first generic to file a Paragraph IV certification can capture 80% of that market within months. Prices can drop 80-90%. The company that wins gets to be the only one selling the generic for half a year. That’s why companies used to camp outside FDA offices, waiting for the first moment they could submit their application. In 2003, the FDA changed the rule: if two companies file on the same day, they split the 180 days. But the race is still on.

The 30-Month Stay: When Patents Delay Generics

When a brand-name company gets notified of a Paragraph IV challenge, they have 45 days to sue for patent infringement. If they do, the FDA is legally required to delay approval of the generic for up to 30 months. This is called the 30-month stay.

Here’s the twist: the 30-month clock doesn’t stop just because the court case is settled. It runs until the patent expires, or until a judge rules the patent is invalid or not infringed. In practice, many patent lawsuits take about 31 months to resolve-exactly long enough to push the generic out past the patent expiration. This isn’t always abuse. Sometimes, the patent is valid. But critics say it’s also used to delay competition.

There’s another layer: patent thickets. Brand manufacturers sometimes file dozens of secondary patents-on coating, packaging, dosing schedules-just to keep generics out longer. The average drug had 1.5 patents listed in the Orange Book when first approved. By the time generics enter, that number jumps to 3.5. It’s not fraud. It’s strategy.

Who Wins? Patients, Insurers, and the Public

The numbers speak for themselves. Since 1984, generic drugs have saved the U.S. healthcare system over $1.7 trillion in just the last decade. In 2023 alone, generics saved $158 billion. Medicare Part D beneficiaries saved an average of $3,200 per person last year because their prescriptions were filled with generics.

By volume, generics make up 90% of all prescriptions. By cost, they’re only 23% of total drug spending. That’s the power of competition. The generic industry now represents a $70 billion market in the U.S., with over 11,000 approved products. The FDA approved 746 ANDAs in 2023-up from just 300 in 2005.

And it’s not just about price. It’s about access. When a drug becomes generic, it moves from being a luxury to a necessity. Insulin, statins, antibiotics, blood pressure pills-all of these are now affordable because of Hatch-Waxman.

Where the System Falters

But it’s not perfect. One major issue: pay-for-delay. Sometimes, the brand-name company pays the generic company to delay their entry. They sign a deal: “We’ll pay you $50 million not to sell your generic for two more years.” The FTC and DOJ have sued over this, and courts have ruled these deals illegal in many cases. But they still happen.

Another problem: refusal to supply. Some brand companies refuse to sell samples of their drug to generic manufacturers. Why? Because you need the brand drug to run bioequivalence tests. In 2019, Congress passed the CREATES Act to stop this. The FDA now actively enforces it, issuing warnings and even blocking approvals if samples aren’t provided.

And then there’s complexity. Hatch-Waxman was built for small-molecule drugs-pills you swallow. It doesn’t work well for biologics, complex proteins made from living cells. That’s why the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) was passed in 2010. But even that system has its own delays and legal battles.

What’s Next? More Challenges, More Innovation

The FDA is working to speed things up. Thanks to the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA), the average review time for an ANDA dropped from 36 months in 2012 to 18 months in 2023. More guidance documents, better communication, and more funding mean faster approvals.

But as more complex drugs come off patent-like injectables, inhalers, and topical creams-the system will need to adapt. The 80-125% bioequivalence window might not be enough. The Orange Book might need to list more than just patents. The 180-day exclusivity might need to be restructured to prevent abuse.

The Hatch-Waxman Act didn’t just create a law. It created a culture of competition. It forced innovation and access to walk hand-in-hand. And for 40 years, it’s worked.

What does ANDA stand for, and why is it important?

ANDA stands for Abbreviated New Drug Application. It’s the legal pathway created by the Hatch-Waxman Act that lets generic drug makers get approval without repeating expensive clinical trials. Instead, they prove their product is bioequivalent to the brand-name drug. Without ANDA, generics wouldn’t exist at today’s scale.

How does the 180-day exclusivity period work?

The first generic company to file an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification (challenging a patent) gets 180 days of exclusive rights to sell that generic. During that time, the FDA can’t approve any other generic versions of the same drug. This incentive drives companies to challenge weak patents early, which speeds up competition and lowers prices.

What is the Orange Book, and how does it affect generic approval?

The Orange Book is the FDA’s official list of approved drug products and their associated patents. Generic manufacturers must review it before filing an ANDA. They must certify how they relate to each listed patent. If they challenge a patent (Paragraph IV), it triggers legal action and can lead to the 180-day exclusivity reward. It’s the rulebook for patent timing.

Can brand-name companies block generics indefinitely?

Not indefinitely, but they can delay them. The 30-month stay can push approval past patent expiration if litigation drags on. Some companies use patent thickets-filing multiple secondary patents-to extend protection. But courts and the FDA are cracking down. The CREATES Act and FTC lawsuits have made these tactics riskier and less effective than they used to be.

Why don’t other countries use the Hatch-Waxman system?

Many countries have simpler generic pathways without patent challenges or exclusivity rewards. The EU, for example, doesn’t give 180-day exclusivity or encourage patent litigation. The U.S. system is unique because it ties generic entry directly to patent disputes. It’s designed to balance innovation incentives with competition-something other systems don’t prioritize.

Is the Hatch-Waxman Act still relevant today?

Absolutely. It’s the foundation of the modern generic drug industry. Over 90% of U.S. prescriptions are generics. Without Hatch-Waxman, those drugs wouldn’t exist at affordable prices. The FDA still approves over 700 ANDAs each year. While new challenges like biologics and complex drugs require updates, the core framework remains essential.

Sean Luke

I specialize in pharmaceuticals and have a passion for writing about medications and supplements. My work involves staying updated on the latest in drug developments and therapeutic approaches. I enjoy educating others through engaging content, sharing insights into the complex world of pharmaceuticals. Writing allows me to explore and communicate intricate topics in an understandable manner.

view all posts