Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia Symptom Checker

How This Tool Works

This tool helps identify symptoms of opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH), a condition where long-term opioid use actually increases pain sensitivity. It's not the same as tolerance, where you need higher doses for the same pain relief.

Answer these questions based on your experience. Your responses will help assess your risk of OIH.

Pain Characteristics

Response to Opioid Dose Changes

Additional Factors

It sounds impossible: you’re taking more opioids to control your pain, but it’s getting worse. Not just a little - your whole body feels more sensitive. A light touch hurts. The same movement that used to cause mild discomfort now feels sharp and burning. You’re not imagining it. This isn’t tolerance. It’s something else: opioid-induced hyperalgesia.

What Exactly Is Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia?

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) is a paradoxical reaction where long-term opioid use makes your nervous system more sensitive to pain instead of less. It’s not the same as tolerance, where you need higher doses to get the same pain relief. With OIH, your pain threshold drops. Things that never hurt before - like a blanket on your skin or a gentle bump - now trigger real pain. The pain also spreads. If you originally had lower back pain, now your legs, hips, or even arms might start hurting too. This isn’t rare. Studies show it happens in 2% to 10% of people on long-term opioid therapy. It’s more common with high doses, especially when given through IV or injections. People with kidney problems are at higher risk because opioid metabolites build up in the body. Morphine-3-glucuronide and hydromorphone-3-glucuronide - byproducts of these drugs - can directly stimulate pain pathways in the spinal cord.How Does Opioid Use Turn Pain Up Instead of Down?

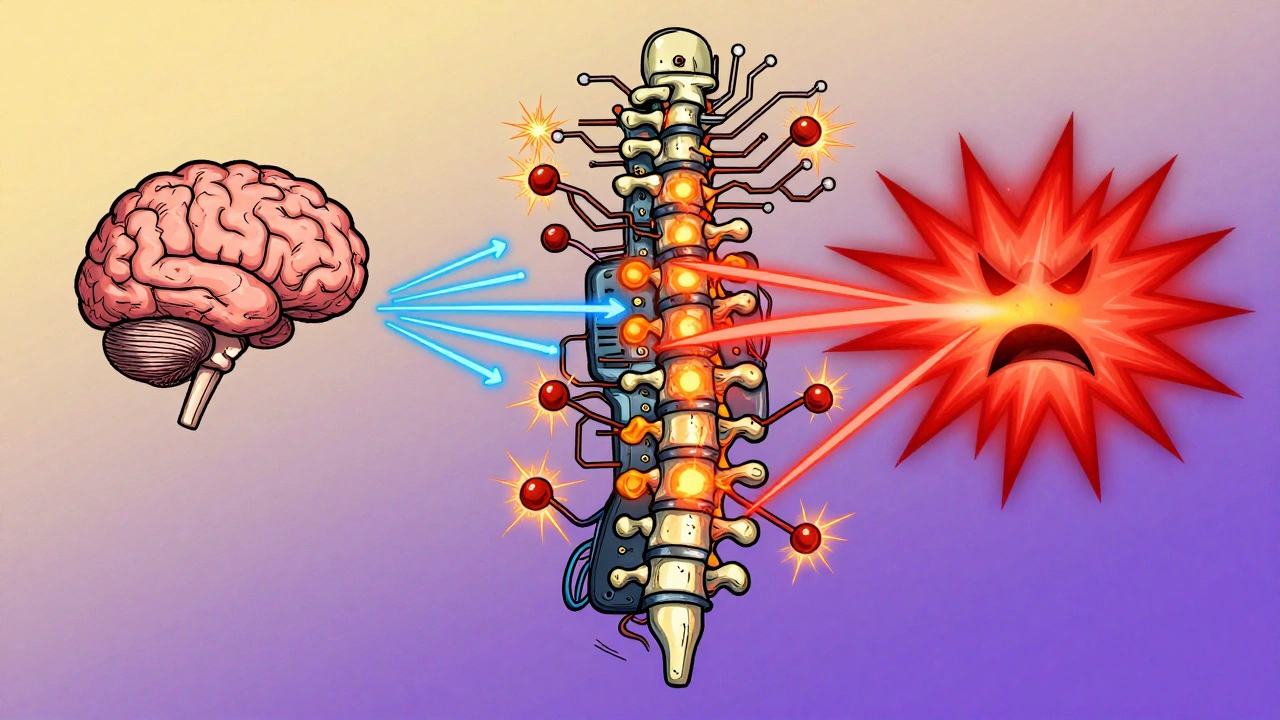

Your nervous system doesn’t just shut down pain signals when opioids are around. It fights back. Here’s how:- NMDA receptors wake up. Opioids bind to brain and spinal cord receptors, but they also trigger a chain reaction that activates NMDA receptors - the same ones involved in chronic nerve pain. This turns up the volume on pain signals.

- Dynorphin gets released. This natural brain chemical, usually linked to stress and depression, increases when opioids are present. Dynorphin makes nerve cells more excitable, sending more pain signals.

- Descending pain pathways flip. Normally, your brain sends signals down the spine to quiet pain. With OIH, those signals become louder, not quieter. The rostral ventromedial medulla - a brain region that controls pain - starts promoting pain instead of blocking it.

- Your genes matter. Some people have a version of the COMT gene that breaks down dopamine and norepinephrine slower. This leads to higher levels of these chemicals in the brain, which can amplify pain sensitivity. If you’ve always been more sensitive to pain, you might be at higher risk for OIH.

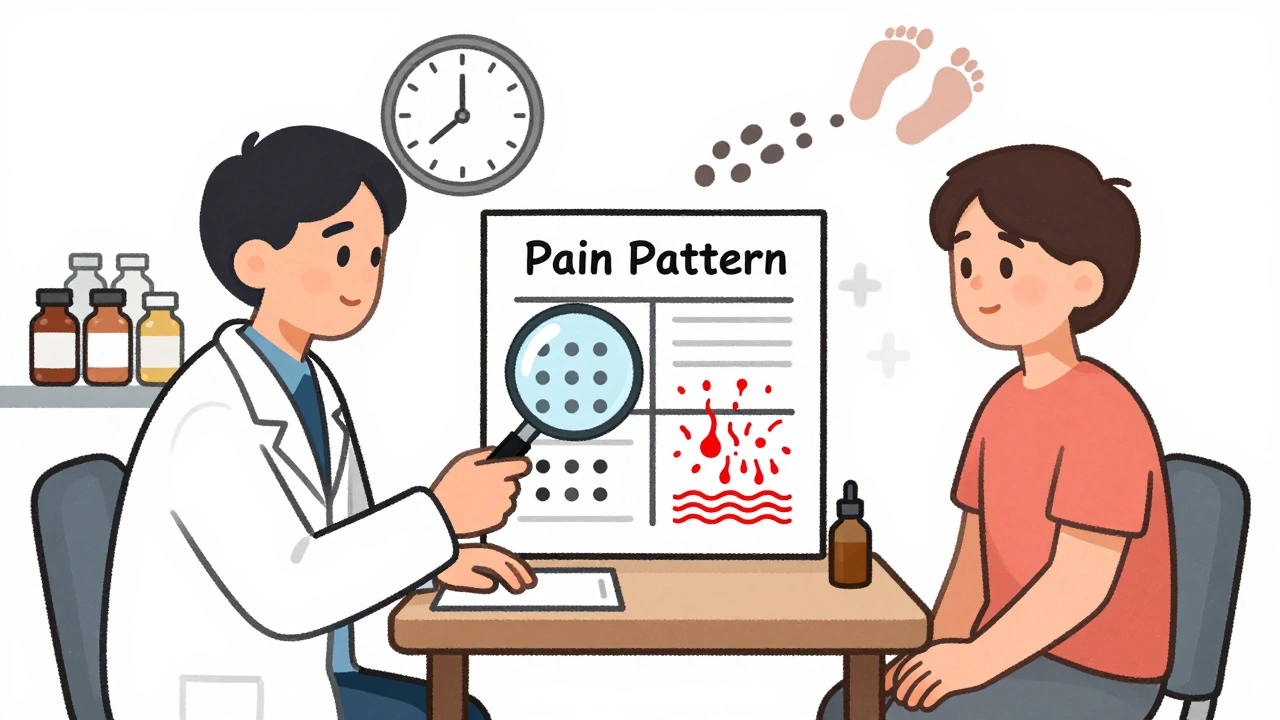

How Do You Know It’s OIH and Not Just Tolerance?

Doctors often confuse OIH with tolerance. But there are key differences:| Feature | Opioid Tolerance | Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia |

|---|---|---|

| Pain pattern | Same location, worsening intensity | Pain spreads beyond original area |

| Response to touch | No change | Allodynia - light touch causes pain |

| Effect of dose increase | Temporary relief | Pain gets worse |

| Effect of dose reduction | Pain returns | Pain may improve |

| Response to non-opioid meds | Minimal effect | Often improves with gabapentin, ketamine |

What Happens If You Just Keep Increasing the Dose?

It’s a trap. You increase the dose to fight the pain. The pain gets worse. You increase again. The cycle continues. More opioids mean more NMDA activation, more dynorphin, more central sensitization. You end up on dangerously high doses - sometimes over 200 mg morphine equivalents per day - with no real relief. In surgical patients, studies show those given high doses of opioids during surgery need 20-30% more pain meds afterward. That’s OIH in action. The drug meant to prevent pain ends up making it harder to control.How Is OIH Treated?

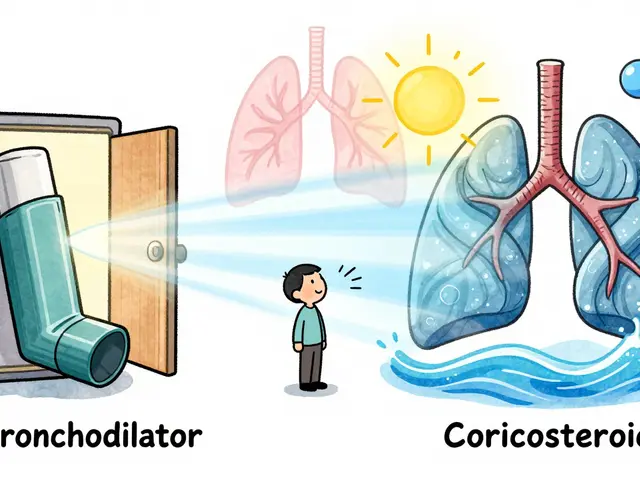

The first step is counterintuitive: reduce the opioid dose. Yes, you read that right. Lowering the dose - even slowly - can reduce the hyperalgesic signal. Many patients report less pain within days or weeks after tapering. The second step is switching opioids. Not all opioids are the same. Methadone is a top choice because it blocks NMDA receptors, just like ketamine. One study found patients on methadone needed 40% less pain medication after surgery compared to those on morphine or oxycodone. Other options include:- Ketamine - given in low doses (0.1-0.5 mg/kg/hour), it blocks NMDA receptors and can break the pain cycle. Used in clinics under supervision.

- Gabapentin or pregabalin - these calm overactive nerves by targeting calcium channels. Doses range from 900-3600 mg/day for gabapentin, 150-600 mg/day for pregabalin.

- Magnesium sulfate - an IV infusion can help reduce acute hyperalgesia, especially in hospital settings.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) - helps retrain how your brain processes pain signals. Works best with medication changes.

Why Is OIH Still Controversial?

Some doctors don’t believe it’s real. They say, “It’s just uncontrolled pain.” But animal studies since 1971 show it clearly. Human studies confirm it too - especially in cancer pain, post-surgery recovery, and chronic pain patients. The problem? It’s hard to prove in a single patient. There’s no blood test. No scan. No clear biomarker. Diagnosis relies on pattern recognition: worsening pain with dose increases, spread of pain, allodynia. A 2020 survey found only 35% of pain specialists felt confident diagnosing OIH. That’s a problem. Patients get labeled as “drug-seeking” or “non-compliant” when they’re actually experiencing a biological side effect of their treatment.What Should You Do If You Suspect OIH?

If you’re on long-term opioids and your pain is getting worse despite higher doses:- Track your pain. Note where it hurts, how intense it is (1-10 scale), and whether light touch triggers it.

- Don’t increase your dose on your own. Talk to your doctor.

- Ask: “Could this be opioid-induced hyperalgesia?”

- Request a review of your opioid regimen. Ask about switching to methadone or adding gabapentin.

- Consider a pain specialist if your current doctor dismisses your concerns.

Looking Ahead: What’s Next for OIH?

Researchers are working on better ways to spot OIH early. Some are testing genetic markers like COMT variants to predict who’s at risk. Others are developing new drugs that block pain without triggering NMDA activation - like kappa-opioid agonists. For now, the best defense is awareness. If you’re on opioids for more than a few months, know the signs. If pain worsens with higher doses, it’s not just tolerance. It might be your body fighting back.Is opioid-induced hyperalgesia the same as addiction?

No. Addiction involves compulsive drug use despite harm, cravings, and loss of control. OIH is a physical change in how your nervous system processes pain. You can have OIH without being addicted, and you can be addicted without having OIH. The treatments are different too - addiction needs behavioral support and sometimes substitution therapy, while OIH needs dose reduction and nerve-calming medications.

Can OIH happen after short-term opioid use?

It’s rare, but possible. Most cases develop after weeks or months of regular use. However, high-dose IV opioids during surgery or in hospital settings have been linked to increased postoperative pain - a form of acute OIH. This is why some anesthesiologists now avoid high-dose opioids during surgery when possible.

Does everyone on opioids get OIH?

No. Only about 2-10% of long-term users develop it. Risk factors include high doses, IV or injectable opioids, kidney problems, and genetic traits like low COMT enzyme activity. People with pre-existing nerve pain or fibromyalgia may also be more susceptible.

Can I stop opioids cold turkey if I have OIH?

Never stop opioids suddenly. Withdrawal can cause severe pain, nausea, anxiety, and even seizures. OIH is best managed with a slow, supervised taper - often over weeks or months. Your doctor may switch you to methadone or add gabapentin first to make the taper easier and reduce rebound pain.

Are there any natural remedies for OIH?

There’s no proven natural cure, but some approaches may help support recovery. Regular low-impact exercise like walking or swimming can reduce central sensitization. Mindfulness and meditation have been shown to lower pain perception in chronic conditions. Omega-3 fatty acids may reduce nerve inflammation. But these should complement - not replace - medical treatment like dose reduction or NMDA blockers.

David Brooks

December 3, 2025 AT 22:44 PMThis is the most important thing I've read all year. I've been on opioids for 8 years and thought I was just getting worse - turns out my body was screaming at me. I tapered down over 6 months and my pain dropped 60%. No joke. I can feel grass again. 🌿

Helen Maples

December 4, 2025 AT 17:50 PMIt’s not ‘just tolerance.’ It’s a neurobiological betrayal. The drugs meant to heal are hijacking your central nervous system. This isn’t anecdotal - it’s peer-reviewed, reproducible, and ignored by half the medical establishment. Wake up, doctors.

Louis Llaine

December 5, 2025 AT 23:22 PMWow. Another ‘opioids are evil’ article. Next they’ll say aspirin causes headaches.

Ted Rosenwasser

December 6, 2025 AT 22:27 PMLet’s be clear: OIH is a well-documented phenomenon in the literature since the 90s. The NMDA-glutamate-dynorphin cascade is textbook neuropharmacology. Anyone who dismisses this hasn’t read a single paper past 2005. The real tragedy is that primary care docs still treat pain like it’s 1998.

Olivia Hand

December 8, 2025 AT 19:21 PMI’ve had chronic back pain for 12 years. I was on 120mg oxycodone daily. Then I started gabapentin and cut my dose by half. The allodynia stopped within 10 days. I didn’t know what to call it - now I do. Thank you for naming the monster.

Kurt Russell

December 9, 2025 AT 20:36 PMTHIS. This is the story so many of us live. I was labeled a drug seeker. My doctor threatened to cut me off. I cried in the parking lot. Then I found a pain specialist who knew about OIH. We switched me to methadone. I haven’t felt this calm in a decade. You’re not broken. Your nervous system just got tricked. And it can heal.

Sadie Nastor

December 10, 2025 AT 08:19 AMi never knew this was a thing… like… at all. my aunt was on opioids for years and just kept getting worse. we thought she was addicted. turns out she was just… in pain. like, more pain. this makes so much sense now. 🥺

Desmond Khoo

December 11, 2025 AT 01:59 AMMy cousin got OIH after a back surgery. They kept giving her more fentanyl. She ended up in the ER with allodynia so bad she couldn’t wear socks. They finally figured it out after 3 months. She’s off opioids now and doing yoga. Life’s different. Better.

Stacy here

December 12, 2025 AT 01:05 AMThey don’t want you to know this. Big Pharma doesn’t profit from methadone or gabapentin. They profit from high-dose oxycodone. The same companies that pushed opioids in the 90s are now quietly funding studies to ‘debunk’ OIH. It’s not a coincidence. This is systemic. You’re being manipulated. And your pain? It’s real - but it’s being weaponized against you.

Wesley Phillips

December 12, 2025 AT 17:50 PMSo basically opioids turn your body into a pain amplifier? That’s wild. I thought I was just weak. Turns out I was just dosed wrong. I’m gonna ask my doc about switching to methadone. No more oxycodone. Done.

Nicholas Heer

December 13, 2025 AT 06:29 AMTHIS IS THE NEW WORLD ORDER. They give you opioids so you get addicted then they blame you for the pain. Then they force you into rehab while the DEA profits. You think this is medicine? It’s a control mechanism. They want you docile. They want you dependent. They want you quiet. Don’t fall for it.

Ryan Sullivan

December 13, 2025 AT 20:14 PMThe methodology of the cited studies is weak. Retrospective self-reports, small sample sizes, no control for confounding variables like depression or fibromyalgia comorbidity. This reads like a blog post masquerading as science. OIH is a fringe concept pushed by anti-opioid activists. The evidence is not robust.

Ashley Farmer

December 14, 2025 AT 17:26 PMTo anyone reading this and feeling alone - you’re not. This isn’t your fault. Your body didn’t fail you. The system did. There are people who understand. There are treatments that work. You deserve relief. Take a breath. Reach out. You’ve got this.