When someone you love dies, it’s normal to feel shattered. You cry. You can’t sleep. You lose interest in food, in friends, in life itself. But is this grief-or is it depression? The line between them is blurry, and mistaking one for the other can mean getting the wrong kind of help. Too many people are told to just wait it out, or worse, handed antidepressants when what they really need is to talk through the loss. Others are told they’re just grieving, when their mind has slipped into a deeper, darker place that won’t lift without real intervention.

What Grief Actually Feels Like

Grief isn’t a straight line. It doesn’t follow stages like denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance-that model was never meant to be a checklist. Real grief comes in waves. One moment you’re laughing at a memory of your partner’s terrible singing. The next, you’re sobbing in the grocery store because you forgot they’re gone. That back-and-forth? That’s grief. It’s painful, yes, but it’s also full of love. You don’t just miss them-you remember them. And those memories, even the bittersweet ones, still feel warm.

People in grief often still want to be around others. They might say, “I just need to be alone,” but they’ll take a cup of tea from a friend. They’ll answer texts. They’ll sit quietly in a room with someone who doesn’t try to fix anything. That’s because grief is tied to a specific person. The pain isn’t about you being broken-it’s about them being gone.

What Depression Looks Like When It’s Not Grief

Depression doesn’t come in waves. It comes in a heavy, flat fog. There’s no spark, no flicker of a good memory. You don’t miss someone-you feel worthless. You don’t want to get out of bed because the world feels pointless, not because your heart is broken. Your appetite changes not because you can’t stomach food without them, but because nothing tastes like anything anymore. Sleep isn’t disrupted by tears-it’s disrupted by exhaustion. You can’t concentrate because your brain feels coated in mud.

People with depression pull away. They stop answering calls. They cancel plans. They don’t want company because being around people feels like too much effort-or worse, like a reminder that they’re failing at life. The thoughts aren’t about the person they lost. They’re about themselves: “I’m a burden.” “I should’ve done more.” “No one would miss me if I disappeared.”

The Clinical Difference: What Doctors Look For

In 2022, the World Health Organization officially recognized Prolonged Grief Disorder a condition marked by persistent, intense yearning for a deceased loved one, lasting at least six months in adults and impairing daily functioning. This wasn’t just a new label-it was a correction. For decades, grief was lumped in with depression. Now, doctors know they’re different.

Here’s what sets them apart, based on the DSM-5-TR the updated diagnostic manual used by mental health professionals in the U.S. and many other countries and ICD-11 the international classification system adopted by the WHO in 2022:

- Prolonged Grief Disorder: Intense longing for the deceased, preoccupation with thoughts of them, emotional pain tied to the loss, difficulty accepting the death, numbness, bitterness. Symptoms last six months or more.

- Major Depressive Disorder: Depressed mood nearly every day, loss of interest in almost everything, weight changes, sleep problems, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, trouble thinking, recurrent thoughts of death. Symptoms last two weeks or more.

Here’s the key: In grief, the sadness is about the person. In depression, the sadness is about you.

A 2017 study of 217 bereaved people found that 87.3% of those with prolonged grief said their main symptom was longing for the deceased. Only 12.1% of those with depression said the same. Meanwhile, 92.6% of people with depression reported feeling worthless. Only 18.4% of those with grief did.

What Doesn’t Work

Antidepressants aren’t the answer for uncomplicated grief. The NICE guidelines the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, which sets evidence-based treatment standards made this clear in 2022: giving SSRIs like sertraline to someone who’s grieving without depression doesn’t help. In fact, it might delay healing. Around 73% of people who’ve lost a loved one start feeling better within six months without medication.

And telling someone to “stay strong” or “they’re in a better place” doesn’t help either. Grief isn’t something to fix. It’s something to sit with. But if someone’s stuck-unable to return to work, avoid all reminders of the person, stop eating, or talk about anything else-that’s not normal grief. That’s prolonged grief.

What Actually Helps

For prolonged grief, the most effective treatment is Complicated Grief Treatment (CGT) a specialized 16-session therapy developed at Columbia University that helps people process loss and rebuild meaning. It’s not talk therapy in the usual sense. It’s structured. It helps you face the pain of the loss instead of avoiding it. It guides you to rebuild your life without the person, not replace them.

A 2014 study in JAMA found that 70.3% of people with prolonged grief who completed CGT saw their symptoms drop significantly. Compare that to depression treatment: the STAR*D trial a large U.S. study on depression treatment outcomes published in 2006 showed that combining sertraline with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) helped 58.1% of patients recover after 12 weeks.

For depression, CBT and medication work well together. But for grief? Medication alone does almost nothing. Therapy that focuses on the loss-that’s what heals.

How to Know If You Need Help

Here’s a simple checklist. If you’ve lost someone and you’re wondering if you need professional support, ask yourself:

- Do I still smile or laugh when I think of them? (If yes, it’s likely grief.)

- Do I feel worthless, useless, or like I don’t deserve to be alive? (If yes, that’s depression.)

- Do I avoid places, people, or things that remind me of them? (If yes, and it’s been over six months, it could be prolonged grief.)

- Do I feel like I’m just going through the motions, with no joy in anything-even things I used to love? (That’s depression.)

- Have I stopped working, seeing friends, or taking care of myself for more than six months? (That’s a red flag for prolonged grief.)

If you answered yes to any of the last three, talk to a therapist who specializes in grief. Don’t wait. Don’t assume it’ll pass. It might, but it might not. And you don’t have to suffer alone.

Where to Find Help

The Association for Death Education and Counseling a professional organization that certifies grief counselors in the U.S. and internationally has over 4,200 certified counselors as of 2022. Many offer remote sessions. Telehealth platforms like BetterHelp a popular online therapy service that saw a 127% increase in grief-related sessions between 2019 and 2022 now have filters for grief specialists.

There are also free resources. The National Institute of Mental Health a U.S. government agency that funds and publishes research on mental health conditions offers guides on distinguishing grief from depression. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) a U.S. federal agency that funds bereavement programs and crisis support allocated $285 million in 2023 for grief services.

And apps? They’re not replacements for therapy, but they can help. A 2023 trial in JAMA Network Open found that the app GriefShare a digital tool designed specifically for people experiencing prolonged grief reduced symptoms by 42.3% over 12 weeks. Depression apps like MoodKit a cognitive behavioral therapy-based app for managing depressive symptoms helped 53% of depressed users-but only 12% of those with prolonged grief.

You’re Not Broken

Feeling lost after a death doesn’t mean you’re weak. It means you loved deeply. But if that loss has turned into a prison-where every day feels the same, where joy is gone, where you feel like a burden-then you’re not just grieving. You’re suffering. And that’s not your fault.

You don’t have to choose between being strong and being honest. You can feel the weight of the loss and still reach out. You can miss someone every day and still find a reason to keep going. And you don’t have to do it alone.

Can grief turn into depression?

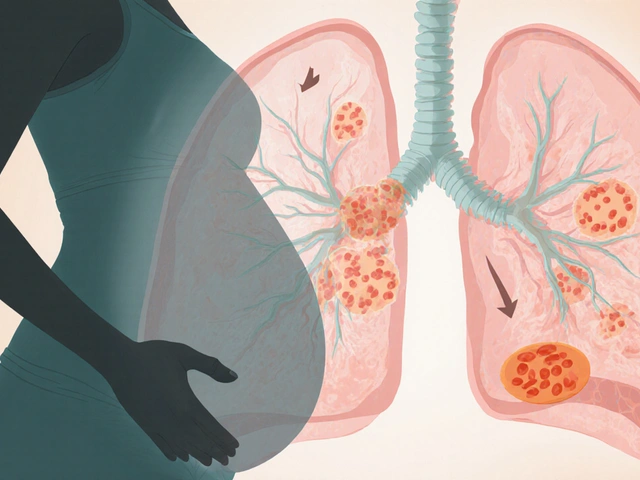

Yes, but they’re not the same thing. Grief can increase the risk of depression, especially if the loss was sudden, traumatic, or if you already had mental health challenges. About 14% of bereaved people develop major depression within a year, according to research from the American Journal of Psychiatry. But grief itself doesn’t “become” depression-it can coexist with it. That’s why professional assessment matters.

How long is too long to grieve?

There’s no timeline for grief. But if after six months you’re still unable to function-can’t work, can’t connect with others, can’t think about anything but the loss-you may have Prolonged Grief Disorder. That’s not about being “stuck.” It’s about your brain needing a different kind of support to process the loss. Six months isn’t arbitrary-it’s the clinical threshold used in the DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 to identify when grief has crossed into a disorder.

Should I take antidepressants if I’m grieving?

Only if you also have major depression. The NICE guidelines in the UK and the APA in the U.S. both recommend against antidepressants for uncomplicated grief. They don’t speed up healing. In fact, they might mask the pain you need to process. If you’re grieving and also have symptoms like constant worthlessness, hopelessness, or suicidal thoughts, then medication might be part of the solution-but only after a proper diagnosis.

What’s the difference between sadness and depression?

Sadness is a reaction. Depression is a condition. Sadness comes and goes. Depression stays. Sadness might make you cry after watching a movie. Depression makes you cry because you can’t remember the last time you felt anything at all. Sadness doesn’t stop you from eating. Depression makes food taste like nothing. Sadness doesn’t make you feel like a burden. Depression does.

Is it normal to feel guilty after someone dies?

Yes, guilt is common in grief. You might replay conversations, wish you’d said more, or blame yourself for not noticing they were struggling. That’s grief. But if the guilt becomes overwhelming-“I’m a terrible person,” “I don’t deserve to live”-that’s depression. Grief guilt is about what you did or didn’t do. Depression guilt is about who you are.

Can children experience prolonged grief?

Absolutely. In children, prolonged grief can look like school refusal, acting out, or regression (like wetting the bed after years of being dry). The diagnostic threshold is longer-12 months instead of six-because their brains process loss differently. But the core symptoms are the same: persistent yearning, preoccupation with the deceased, emotional numbness, and impaired functioning. Kids need specialized grief therapy, not just time.

What if I don’t cry? Does that mean I’m not grieving?

Not at all. Some people express grief through anger, numbness, or withdrawal. Others feel it internally and don’t cry. That doesn’t mean they’re not grieving-it means they’re grieving differently. Cultural background, personality, and past experiences shape how grief shows up. What matters is whether the pain is tied to the person you lost, or whether it’s become a general sense of emptiness and worthlessness.

What to Do Next

If you’re reading this and you’re not sure whether you’re grieving or depressed, start here: make an appointment with your GP or a mental health professional. Bring a list of your symptoms. Note when they started. Note what thoughts keep coming back. Did they start after a loss? Or did they come out of nowhere?

If you’re supporting someone who’s grieving, don’t tell them to be strong. Don’t say “they’re in a better place.” Say, “I’m here.” Sit with them. Let them talk. Let them cry. Let them not cry. And if they seem to be sinking-staying in bed for days, not eating, talking about not wanting to live-ask directly: “Are you thinking about hurting yourself?” That question doesn’t plant the idea. It opens the door.

You don’t have to understand grief to help someone through it. You just have to stay present. And if you’re the one hurting? Reach out. You’re not weak for needing help. You’re human.

Courtney Black

December 10, 2025 AT 04:55 AMGrief isn't a disorder to be fixed. It's the price of love. And if you're lucky, you'll carry it forever-not as a burden, but as proof you mattered to someone, and they mattered to you.

Stop trying to diagnose it. Start sitting with it.

iswarya bala

December 12, 2025 AT 02:50 AMthx for this post!! i lost my dad last year and ppl kept sayin ‘u’ll be ok in time’… but it aint bout time. its bout learnin to carry him with u. i cry at the grocery store too 😭

om guru

December 13, 2025 AT 09:14 AMIt is imperative to recognize the clinical distinction between prolonged grief disorder and major depressive disorder. Misapplication of pharmacological intervention may impede natural psychological adaptation. Evidence-based psychotherapeutic modalities remain the gold standard.

Consult a licensed clinician prior to self-diagnosis.

Jennifer Blandford

December 14, 2025 AT 19:28 PMMy grandma died and I didn't cry for three months. I just… stared at her chair. Then one day I laughed at a memory of her stealing my fries and I felt like I could breathe again.

That’s grief. Not broken. Just… changed.

And yeah, antidepressants? Nah. I needed someone to say, ‘Tell me about her again.’ Not ‘Take this pill.’

Ronald Ezamaru

December 15, 2025 AT 17:54 PMThe 2017 JAMA study cited here is robust. 87% of prolonged grief patients reported longing as the core symptom-far higher than any depressive symptom cluster. This isn't anecdotal. It's epidemiological.

Also, the CGT success rate of 70.3% outperforms SSRIs in grief by a factor of 3x. Why are we still prescribing antidepressants for bereavement? The data is clear.

Therapy isn't optional. It's essential.

Iris Carmen

December 17, 2025 AT 05:13 AMso i lost my bestie last year and i just stopped talking to everyone. didn’t answer texts. didn’t shower. just sat on the floor with her hoodie.

people called it depression. i called it love.

it took 8 months. but i started cooking her recipes again. now i cry when i burn the cookies. not because i’m sad. because i miss her.

grief ain’t broken. it’s just… heavy.

Rich Paul

December 18, 2025 AT 03:27 AMlook, i get it. grief is ‘special.’ but if you’re not functioning after 6 months, you’re not ‘deeply grieving,’ you’re just avoiding therapy. CGT sounds like a fancy buzzword for ‘talk to someone.’

also, apps? GriefShare? That’s like using a mood tracker to cure cancer. stop romanticizing suffering. get help. period.

Delaine Kiara

December 19, 2025 AT 12:42 PMOkay but what if you grieve and you’re also depressed? What if you’re crying because you miss them AND because you think you’re worthless?

That’s not a checklist. That’s a fucking nightmare.

And no, your GP isn’t trained for this. You need someone who’s lost someone too. Otherwise you’re just a case file.

Also-why is no one talking about the fact that grief is the only trauma where you’re told to ‘get over it’?

Ruth Witte

December 21, 2025 AT 10:23 AMYOU ARE NOT ALONE 💔

It’s okay to not be okay.

Reach out. Cry. Scream into a pillow. Eat ice cream for dinner.

Therapy isn’t weak. It’s WARRIOR ENERGY 🛡️✨

And if you’re reading this? You’re already healing. I believe in you. 💪❤️

Noah Raines

December 22, 2025 AT 13:09 PMPeople say ‘grief takes time’ like it’s a damn vacation. Nah. It’s a fucking war. And if your brain is telling you you’re worthless, that’s not grief. That’s depression. And you don’t get a medal for suffering in silence.

Go see someone. Now. I’m not asking. I’m telling you.

You’re worth more than your pain.

Katherine Rodgers

December 23, 2025 AT 01:37 AMWow. Another ‘grief is sacred’ manifesto. Let me guess-you’ve never taken an SSRI and also never been clinically depressed?

So if someone takes medication and feels better? They’re ‘avoiding the pain’? Or just… healing?

Stop acting like grief is a spiritual rite and not a biological response to loss. Some people need meds. Get over it.

Darcie Streeter-Oxland

December 25, 2025 AT 00:52 AMThe assertion that antidepressants are ineffective in uncomplicated grief is not universally supported in the literature. The 2022 NICE guidelines are, after all, context-specific to the UK healthcare model. One must consider the heterogeneity of bereavement responses across cultural and socioeconomic strata.

Moreover, the 73% recovery rate cited lacks a control group. One wonders about attrition bias.

Mona Schmidt

December 26, 2025 AT 12:34 PMThank you for writing this with such clarity. As someone who works with bereaved youth, I see how often grief is mislabeled as depression-and then treated with medication instead of space. Children especially need narrative-based grief support, not pills.

Also, the part about guilt being tied to identity versus action? That’s the most accurate thing I’ve read all year.

Guylaine Lapointe

December 27, 2025 AT 17:06 PMHow is it possible that in 2025, we still need to explain that grief isn't depression? The fact that this post even exists speaks to a systemic failure in mental health education.

And yet, I still see therapists prescribing SSRIs to widows at 6 weeks. Shameful.

Also, ‘GriefShare’? That’s a church app. Not a clinical tool. Don’t confuse spiritual comfort with evidence-based care.

Sarah Gray

December 28, 2025 AT 09:08 AMHow quaint. You’ve written a 2000-word essay to say ‘grief is sad and depression is worse.’

And yet, you ignore that both can coexist. You ignore that culture shapes expression. You ignore that many don’t have access to CGT because it costs $150/session.

So you’ve written poetry instead of policy.

Well done.