When your liver fails, there’s no backup system. No second chance. No pill that can replace its job. For thousands of people each year, liver transplantation is the only path back to life. It’s not a simple fix-it’s a complex, high-stakes journey that begins long before the operating room and lasts a lifetime.

Who Gets a Liver Transplant?

Not everyone with liver disease qualifies. The system is strict, and for good reason. There aren’t enough donor livers to go around. In the U.S., about 8,000 transplants happen each year, but over 10,000 people are on the waiting list. So who makes the cut? The answer comes down to two things: how sick you are, and whether you can survive the procedure and stick to the lifelong rules afterward. Your medical urgency is measured by the MELD score-a number between 6 and 40. It’s calculated using blood tests for bilirubin, creatinine, and INR. The higher the score, the closer you are to death without a transplant. A MELD score of 25 or above puts you in the top tier for urgency. If you’re at 30, you’re in critical condition. But your score isn’t the whole story. You also need to pass a psychosocial evaluation. That means proving you have stable housing, reliable transportation, and a support system. If you’ve struggled with alcohol or drugs, you’ll need at least six months of documented sobriety. Some centers are starting to question this rule-studies show patients with three months of abstinence have survival rates nearly identical to those with six. But most still require the longer wait. Certain conditions automatically disqualify you. Active cancer that’s spread beyond the liver? No. Untreated HIV or hepatitis B with high viral load? Usually no. Severe heart or lung disease that makes surgery too risky? Also no. Even obesity can be a barrier-donors need to be healthy, and recipients with a BMI over 35 often face extra hurdles. If you have liver cancer, the rules get even tighter. The Milan criteria apply: one tumor under 5 cm, or up to three tumors each under 3 cm, with no spread to blood vessels. If your tumor is bigger or has invaded vessels, you’re typically ineligible unless you respond to treatment and bring your alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level below 500. Some centers now offer special exceptions, but they’re rare.The Surgery: What Happens in the Operating Room

Liver transplant surgery is one of the most complex procedures in medicine. It usually takes between six and twelve hours. The goal is simple: remove the damaged liver and replace it with a healthy one. But the steps are anything but. There are two types of donors: deceased and living. About 85% of transplants come from deceased donors. The rest come from living donors-usually a family member or close friend who donates a portion of their liver. The liver is the only organ that can regenerate. After surgery, both the donor’s remaining liver and the transplanted piece will grow back to full size within weeks. For adult recipients, surgeons typically remove the right lobe (55-70%) from the donor. For children, they take the left lateral segment. The donor’s remnant liver must be at least 35% of their original liver volume to ensure safe recovery. Donors must be between 18 and 55, have a BMI under 30, and be free of liver, heart, or kidney disease. The risk of death for a living donor is about 0.2%. Complications like bile leaks or infections happen in 20-30% of cases. The surgery itself has three phases. First, the diseased liver is removed (hepatectomy). Then comes the anhepatic phase-when the patient has no liver at all. This is the most dangerous part. Blood flow is rerouted, and the body relies on temporary support. Finally, the new liver is stitched in. Most surgeons use the “piggyback” technique, which leaves the patient’s inferior vena cava intact. This reduces bleeding and speeds recovery. New tech is making a difference. Machine perfusion, which keeps donor livers alive with oxygenated fluid outside the body, is now used in 30% of centers. It’s especially helpful for livers from donation after circulatory death (DCD) donors. These livers used to have higher complication rates, but with perfusion, biliary problems dropped from 25% to 18%. After surgery, patients spend 5-7 days in the ICU. Total hospital stay is usually 14-21 days if there are no complications. Donors typically go home after 7-10 days and return to normal activity in 6-8 weeks.Immunosuppression: The Lifelong Trade-Off

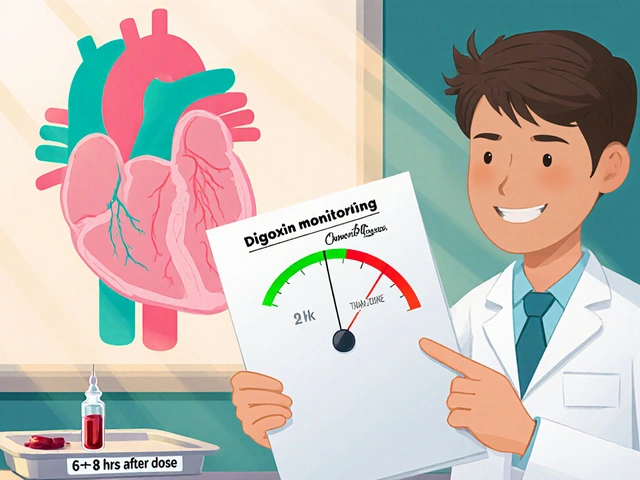

Your body sees the new liver as an invader. Left unchecked, your immune system will attack it. That’s why you need immunosuppressants-for life. The standard regimen is triple therapy: tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. Tacrolimus is the backbone. Doctors aim for a blood level of 5-10 ng/mL in the first year, then lower it to 4-8 ng/mL. Too high, and you risk kidney damage. Too low, and rejection kicks in. Mycophenolate stops immune cells from multiplying. It’s taken twice daily. Side effects? Nausea, diarrhea, and low white blood cell counts. About 30% of patients get stomach issues. Ten percent need dose adjustments because their bone marrow slows down. Prednisone, a steroid, was once a staple. But now, 45% of U.S. transplant centers use steroid-sparing protocols. They drop prednisone after 30 days. Why? Because steroids cause weight gain, diabetes, and bone loss. Removing them cuts the risk of new-onset diabetes from 28% to 17%. Rejection happens in 15% of patients within the first year. Most are caught early through blood tests and biopsies. Treatment usually means boosting tacrolimus or adding sirolimus, another immunosuppressant that’s gentler on the kidneys. Long-term side effects are real. After five years, 35% of patients have kidney damage from tacrolimus. One in four develop diabetes. One in five get tremors or trouble sleeping. Mycophenolate can cause anemia. And all of these drugs raise your risk of infections and skin cancer. The goal isn’t to eliminate rejection-it’s to balance it. You want just enough suppression to protect the liver, but not so much that your body can’t fight off colds or flu.

Living Donor vs. Deceased Donor: The Real Differences

Choosing between a living donor and a deceased donor isn’t just about timing-it’s about trade-offs. With a deceased donor, you wait. And wait. The national average wait for a liver is 12 months. But it varies wildly by region. In the Midwest, you might wait 8 months. In California, it’s 18. That’s because organ distribution is based on geography, not just medical need. Living donor transplants cut that wait to about 3 months. That’s life-changing for someone with a MELD score of 30. But it comes with risks-for the donor. Donors face a 0.2% chance of death. About 1 in 5 have complications like bile leaks, bleeding, or hernias. That’s why many centers only offer living donation when the patient is unlikely to survive the wait. DCD livers (from donors whose hearts stopped) are becoming more common-now 12% of all transplants. They used to have higher failure rates, but with machine perfusion, their 5-year survival is now nearly equal to brain-dead donors.Life After Transplant: The Real Challenge

Getting the liver is only half the battle. Staying alive with it is the harder part. You’ll need weekly blood tests for the first three months. Then biweekly, then monthly. You’ll see your transplant team every few weeks for the first year. After that, every three months. Medication costs? $25,000 to $30,000 a year-just for the immunosuppressants. Insurance often covers most of it, but 32% of patients report being denied coverage for pre-transplant evaluations. That’s a huge barrier. You must take your pills exactly on time. Miss even one dose, and rejection can start. The threshold for success? 95% adherence. That means no skipping, no forgetting, no running out. You also need to watch for signs of trouble: fever over 100.4°F, yellow skin, dark urine, extreme fatigue, or swelling in your belly. These aren’t normal. Call your team immediately. Infection prevention is critical. Avoid raw seafood. Don’t clean bird cages or change cat litter. Wash hands constantly. Get all recommended vaccines-except live ones. The best outcomes come from centers with dedicated transplant coordinators. These teams handle everything: scheduling, insurance, social support, mental health. Patients at these centers have 87% one-year survival. At centers without them? 82%.

What’s Next for Liver Transplants?

The field is changing fast. New guidelines are relaxing donor age limits-some centers now accept donors up to 65 if they’re healthy. BMI limits are rising too. One study showed donors with BMI up to 32 had the same outcomes as those under 30. Researchers are testing ways to stop immunosuppression altogether. At the University of Chicago, 25% of pediatric transplant patients were able to stop all drugs by age five using a therapy that boosts regulatory T-cells. If this works in adults, it could end the lifelong drug burden. Portable liver perfusion devices are now FDA-approved. They keep livers alive for 24 hours instead of 12, giving teams more time to match donors and recipients. This could reduce waste and help more people. And there’s growing awareness of inequity. In British Columbia, Indigenous patients now get culturally tailored evaluations. Abstinence requirements are adjusted based on personal history. This isn’t just fairness-it’s better outcomes. One thing won’t change: there will never be enough livers. That’s why living donation, better organ preservation, and new treatments matter. But for now, if you’re on the list, the key is patience, discipline, and trusting your team.Frequently Asked Questions

Can you live a normal life after a liver transplant?

Yes, most people return to normal activities within 6-12 months. Many go back to work, travel, and even have children. But you’ll always need to take immunosuppressants, avoid infections, and get regular blood tests. Life isn’t the same as before liver disease-but it’s full again.

How long does a transplanted liver last?

About 70% of transplanted livers are still working after five years. For those who survive the first year, many live 15-20 years or more. The liver doesn’t wear out like a machine-it can function well for decades if you follow your care plan.

Why is the MELD score so important?

The MELD score tells transplant centers who’s most likely to die without a transplant. It’s based on three blood tests that measure liver function. Higher scores mean higher priority. It’s the fairest system we have-no favoritism, no waiting lists based on wealth or location.

Can you drink alcohol after a liver transplant?

Absolutely not. Even small amounts of alcohol can damage your new liver. Alcohol is toxic to liver cells, and your transplanted liver has no reserve. One drink can lead to scarring, failure, and the need for another transplant-which is almost never possible.

What happens if the transplant fails?

If rejection or complications cause the new liver to fail, you may be re-listed for another transplant. But it’s harder. You’ll need to be in good enough health to survive another surgery, and your chances are lower because you’ve already had one transplant. Prevention through strict adherence to medication and follow-up is far better than trying to fix failure.

Malikah Rajap

January 18, 2026 AT 18:22 PMWow, this post made me cry-like, actual tears. I didn’t realize how much goes into just… surviving. My cousin got a liver last year, and I thought it was just ‘get the organ, take pills, done.’ But no. It’s like signing up for a marathon where the finish line keeps moving. And the cost? Holy hell. I’m glad someone finally said it out loud.

Aman Kumar

January 20, 2026 AT 01:20 AMThe MELD score is a statistically valid metric, yet the psychosocial evaluations remain deeply flawed-relying on arbitrary abstinence windows that lack longitudinal validation. The 6-month sobriety requirement is a relic of 1990s moralism, not evidence-based hepatology. Studies from the University of Toronto (2021) and Karolinska (2022) demonstrate non-inferiority at 3 months. Institutional inertia is killing people.

Valerie DeLoach

January 20, 2026 AT 16:52 PMI’ve been a transplant coordinator for 14 years, and this is the most accurate, compassionate summary I’ve ever read. But I want to add something: the real heroes aren’t the surgeons-they’re the spouses, the siblings, the friends who show up every single day to remind someone to take their meds. One woman I worked with had her daughter set phone alarms for her every 12 hours. No one ever thanked that girl. But she saved her mom’s life.

Josh Kenna

January 21, 2026 AT 03:47 AMokay so i just read this whole thing and i have to say… i had no idea. like, i thought liver transplants were like kidney ones-easy peasy. but this? this is brutal. the part about the anhepatic phase? that sounds like a horror movie. and the meds? 25k a year? my insurance denied my mom’s pre-transplant eval too. why is this so hard??

Erwin Kodiat

January 22, 2026 AT 05:48 AMReading this made me want to sign up as a living donor. I’m 32, healthy, no kids. If I can give someone 35% of my liver and get to go back to hiking in 2 months… why wouldn’t I? I know it’s scary, but so is watching someone fade away waiting. Let’s normalize this. Talk to your family. Be the reason someone gets to see their grandkid grow up.

Jackson Doughart

January 22, 2026 AT 14:40 PMWhile the medical details presented are largely accurate, the tone of the article inadvertently perpetuates a narrative of scarcity that may discourage organ donation. The phrase 'there will never be enough livers' is a self-fulfilling prophecy. We must reframe the discourse around abundance, reciprocity, and community responsibility-not just clinical metrics.

Lydia H.

January 23, 2026 AT 23:01 PMMy dad got a liver transplant in 2018. He’s still here. He still drinks coffee, still argues with me about politics, still forgets to take his meds sometimes. But he’s alive. And I think this post misses one thing: the quiet, boring, unglamorous heroism of daily life after. It’s not about surviving the surgery. It’s about showing up for Tuesday.

Phil Hillson

January 24, 2026 AT 17:52 PMSo basically if you're poor or have a history of addiction you're just out of luck? The system is rigged. They let rich people jump the line with living donors while the rest of us wait and die. And don't even get me started on how they treat Black and Indigenous patients. This isn't medicine. It's a lottery with a side of racism.

Jacob Hill

January 25, 2026 AT 01:27 AMJust wanted to add: machine perfusion isn't just for DCD livers anymore-some centers are using it for all donors now. It's cutting ischemia time by half, and the graft survival numbers are insane. Also, the new FDA-approved portable units? They’re the size of a suitcase. Imagine a liver on a plane. Wild.

Lewis Yeaple

January 25, 2026 AT 20:16 PMIt is imperative to clarify that the Milan criteria remain the gold standard for hepatocellular carcinoma eligibility. Deviations from these parameters, while occasionally permitted under compassionate protocols, are associated with significantly higher recurrence rates and inferior overall survival. Any deviation must be justified by Level I evidence and institutional review board approval.

sujit paul

January 27, 2026 AT 01:49 AMHave you ever considered that the entire transplant system is a controlled mechanism to reduce population surplus? The MELD score is manipulated. The waiting lists are artificially inflated. The drugs? Designed to create lifelong dependency. The real cure? A plant-based diet and fasting. But they don’t want you to know that.

Christi Steinbeck

January 27, 2026 AT 14:51 PMOne sentence: If you’re healthy enough to donate, do it. Your liver grows back. Someone’s life doesn’t.