When a generic drug company wants to prove its product works just like the brand-name version, it doesn’t test it on thousands of people. It doesn’t run years-long clinical trials. Instead, it uses a smart, efficient method called a crossover trial design. This approach is the backbone of nearly every bioequivalence study approved by the FDA or EMA today. And if you’re wondering why it’s so common, the answer is simple: it cuts costs, reduces sample sizes, and gives clearer results by using each person as their own control.

How a Crossover Design Works

In a crossover trial, every participant gets both the test drug (the generic) and the reference drug (the brand-name version) - but not at the same time. They take one first, then after a break, they take the other. This isn’t just alternating pills; it’s a carefully timed sequence. The most basic version is called a 2×2 crossover: half the volunteers get the test drug first, then the reference (AB sequence), and the other half get the reference first, then the test (BA sequence). The key? A washout period between doses.

That washout period isn’t just a waiting room. It’s critical. It must be long enough - at least five elimination half-lives of the drug - so that no trace of the first dose remains when the second begins. If it’s too short, leftover drug from the first period can mess up the second. That’s called a carryover effect, and it’s one of the most common reasons bioequivalence studies get rejected by regulators.

Why does this setup work so well? Because it removes the noise. People vary wildly in how they absorb drugs. Age, weight, liver function, gut bacteria - all these things affect results. In a parallel study (where one group gets the test and another gets the reference), those differences can hide the real effect. But in a crossover design, each person is their own control. If someone absorbs drugs slowly, they’ll absorb both drugs slowly. The comparison becomes about the drugs themselves, not the people.

Why Sample Sizes Are So Small

Parallel studies need 60 to 100 volunteers to get reliable results. Crossover studies? Often just 24. Sometimes even 12.

The math behind it is straightforward. When the differences between people are much bigger than the natural variation in how a single person responds to a drug, crossover designs become dramatically more powerful. Research shows that when between-person variability is twice as large as within-person variability, you only need one-sixth the number of participants to achieve the same statistical confidence. That’s not a small gain - it’s transformative.

Take a real example: a generic warfarin study. A parallel design would’ve needed 72 people. The team used a 2×2 crossover instead. They enrolled 24. They saved $287,000 and eight weeks of study time. That’s not just efficiency - it’s practical necessity in an industry where margins are thin and timelines are tight.

What Happens When Drugs Are Highly Variable?

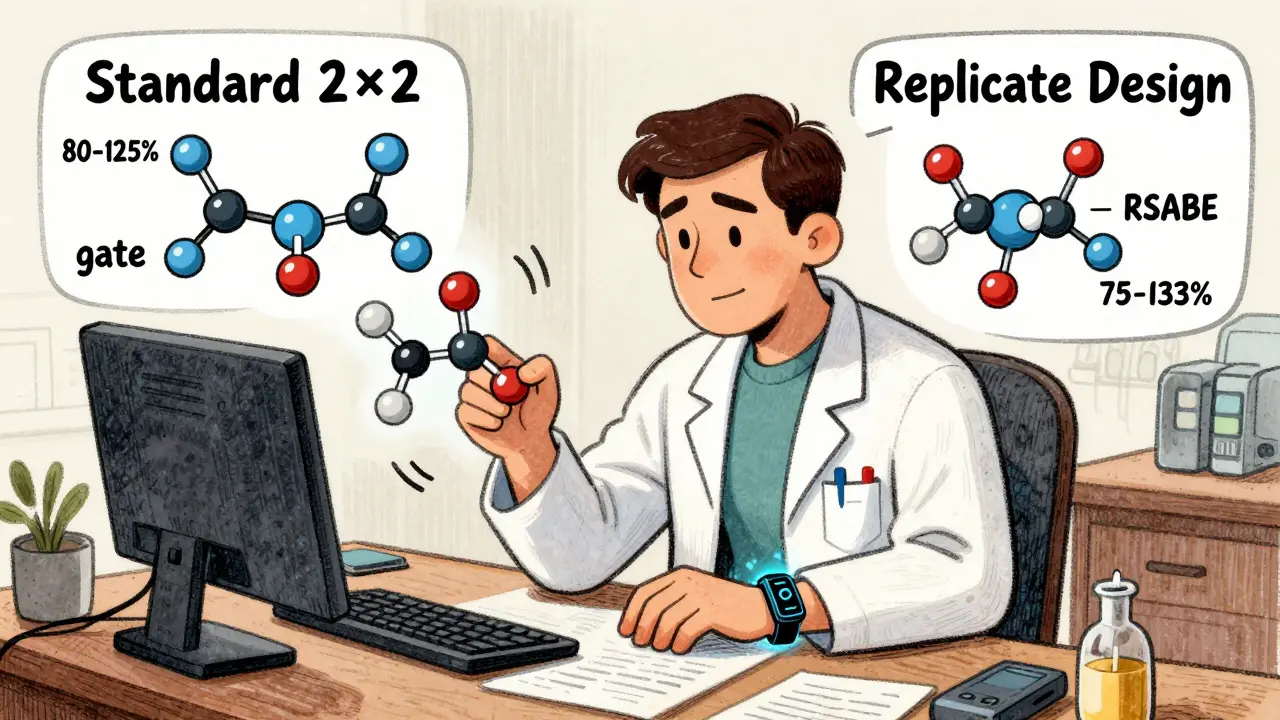

Not all drugs behave the same. Some - like warfarin, clopidogrel, or certain antiretrovirals - show huge swings in how they’re absorbed from person to person. That’s called high intra-subject variability. When the coefficient of variation (CV) exceeds 30%, the standard 2×2 design starts to struggle. The confidence interval might fall outside the acceptable 80-125% range, even if the drugs are truly equivalent.

That’s where replicate designs come in. Instead of two periods, you use four. There are two main types: full replicate (TRTR/RTRT) and partial replicate (TRR/RTR). In both, each drug is given twice. This lets researchers estimate the variability of each drug separately - something the basic crossover can’t do.

Why does that matter? Because regulators now allow something called reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE). Instead of a fixed 80-125% window, the acceptable range expands based on how variable the reference drug is. For a drug with 40% CV, the window might stretch to 75-133%. But you can only use RSABE if you’ve measured within-subject variability - and that’s only possible with replicate designs.

Industry data shows that in 2015, only 12% of highly variable drug approvals used RSABE. By 2022, that number jumped to 47%. And it’s still climbing. The EMA’s 2024 update will make full replicate designs the preferred method for all highly variable drugs. That’s not a trend - it’s the new standard.

The Hidden Costs and Risks

It’s tempting to think crossover designs are always better. But they come with trade-offs.

First, the study duration. A 2×2 crossover with a 14-day washout takes at least 4-6 weeks per person. A replicate design? 8-12 weeks. That means more staff time, more clinic visits, more logistical headaches. One statistician reported a failed study where they underestimated the washout for a drug with a 10-day half-life. Residual drug showed up in the second period. They had to restart - at an extra cost of $195,000.

Second, data analysis is more complex. You can’t just compare averages. You need mixed-effects models - often run in SAS or R - to account for sequence, period, and treatment effects. Missing data? If someone drops out after the first period, their data is usually thrown out. That’s because the whole power of the design relies on paired comparisons. Lose one half of a pair, and you lose the advantage.

Third, carryover effects are still a silent killer. Even with a five-half-life washout, some drugs linger. That’s why every protocol must include a statistical test for sequence-by-treatment interaction. If it’s significant, the study is invalid - no matter how clean the rest of the data looks.

Regulatory Rules That Shape the Design

The FDA and EMA don’t just recommend crossover designs - they require them for most cases. The FDA’s 2013 guidance says bluntly: “A crossover study design is recommended.” The EMA’s 2010 guideline echoes that. Both agencies demand specific statistical thresholds: the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of geometric means (test/reference) must fall between 80% and 125% for both AUC (total exposure) and Cmax (peak concentration).

For narrow therapeutic index drugs - where small differences can cause harm - the FDA recently proposed allowing 3-period replicate designs (TTR/RRT/TRR). That’s new. It’s also a sign of where things are headed: more complexity, more data, more precision.

And the numbers back it up. In 2022-2023, 89% of all generic drug approvals submitted to the FDA used crossover designs. CROs like PAREXEL and Charles River report 75-80% of their bioequivalence work follows this model. It’s not just popular - it’s the default.

What’s Next for Crossover Designs?

The future isn’t about replacing crossover designs - it’s about making them smarter. Adaptive designs are gaining ground. These are studies where the sample size gets adjusted mid-way based on early results. In 2018, only 8% of FDA submissions used this approach. By 2022, it was 23%. That’s a steep climb.

And then there’s digital monitoring. Wearables that track heart rate, activity, and even drug levels in real time could one day reduce the need for washout periods. Imagine knowing exactly when a drug clears from the system - not guessing based on half-lives. That could revolutionize crossover trials. But we’re not there yet.

For now, the crossover design remains the gold standard. It’s proven, efficient, and backed by decades of regulatory experience. It’s not perfect. But for most generic drugs, it’s the only way to prove equivalence without breaking the bank.

What is the most common crossover design used in bioequivalence studies?

The most common design is the two-period, two-sequence (2×2) crossover, where participants are split into two groups: one receives the test drug then the reference (AB), and the other receives the reference then the test (BA). Each period is separated by a washout period of at least five elimination half-lives. This design is used in about 68% of standard bioequivalence studies today.

Why is a washout period so important in a crossover trial?

The washout period ensures that no residual drug from the first treatment affects the results of the second. If drug levels from the first period are still detectable, it creates a carryover effect - a major flaw that can invalidate the entire study. Regulators require washout periods to be based on the drug’s elimination half-life, typically five or more half-lives, and often validated with pilot data to confirm concentrations fall below the lower limit of quantification.

When should a replicate crossover design be used instead of a 2×2 design?

A replicate design (TRTR/RTRT or TRR/RTR) should be used when the drug shows high intra-subject variability - typically when the coefficient of variation exceeds 30%. These designs allow regulators to use reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE), which adjusts the acceptance range based on the drug’s natural variability. This prevents unnecessary study failures and avoids the need for prohibitively large sample sizes in a standard 2×2 design.

Can crossover designs be used for drugs with very long half-lives?

No, crossover designs are generally not suitable for drugs with half-lives longer than two weeks. The required washout period would be impractical - potentially lasting months - making it unfeasible for participants to complete both treatment periods. For these drugs, parallel-group designs are required, even though they need significantly larger sample sizes.

How do regulators determine if two drugs are bioequivalent?

Regulators like the FDA and EMA require the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of geometric means (test/reference) to fall within 80.00% to 125.00% for both AUC (area under the curve) and Cmax (maximum concentration). For highly variable drugs, this range can be widened using reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE), but only if the study uses a replicate crossover design to measure within-subject variability.

Final Thoughts

Crossover trials aren’t magic. They’re a tool - precise, powerful, and deeply rooted in statistical logic. They work because they strip away noise. They’re not for every drug, but for the vast majority of generics, they’re the smartest path forward. The real skill isn’t in running the trial - it’s in designing it right. Get the washout wrong, misjudge the variability, or skip the sequence test, and even the cleanest data won’t pass regulatory review.

For anyone working in generic drug development, understanding crossover design isn’t optional. It’s the foundation. And as complex generics become more common, the demand for replicate designs and adaptive methods will only grow. The next decade won’t replace the crossover - it will refine it.

Jane Lucas

December 27, 2025 AT 00:50 AMso like… you’re telling me we just give people the same drug twice and call it science? wow. i always thought generics were just cheaper versions but now i get it. they’re basically using people as lab rats in a timed pill game. cool.

Kylie Robson

December 28, 2025 AT 00:50 AMActually, the 2×2 crossover is only statistically optimal when intra-subject CV < 30%. Once you hit >30%, the power drops precipitously unless you implement a replicate design with sufficient periods to estimate within-subject variance. The FDA’s RSABE framework only applies when you’ve demonstrated sufficient within-subject variability via TRTR/RTRT or TRR/RTR. Most CROs still default to 2×2 out of convenience, not science.

Caitlin Foster

December 29, 2025 AT 07:15 AMYESSSSSS!!! This is why I love pharmacology!! The elegance of using each person as their own control?!?! I mean, who even thought of this?!? It’s like nature gave us a built-in placebo button and we just learned how to press it. 🤯👏

Miriam Piro

December 30, 2025 AT 08:08 AMThey say it’s about efficiency… but let’s be real - this whole system is rigged. The FDA and Big Pharma are in bed together. Crossover trials? They’re not designed to prove safety. They’re designed to make generics look good enough to pass without real long-term data. Who’s tracking what happens after 6 months? No one. They don’t want you to know that the ‘equivalent’ drug might be slowly wrecking your liver while saving them $200k per study. Wake up.

Andrew Gurung

December 31, 2025 AT 06:30 AMHow quaint. A 2×2 crossover? That’s undergraduate-level bioequivalence. Real scientists use full replicate designs with linear mixed-effects models in R, accounting for period, sequence, and subject effects with Kenward-Roger degrees of freedom. If you’re still using SAS and a fixed-effects model, you’re not just behind - you’re dangerous. 😒

dean du plessis

January 2, 2026 AT 04:23 AMInteresting stuff. I work in a clinic in Cape Town and we see a lot of generic antiretrovirals. The washout periods are brutal for patients - some have to come back every two weeks for months. But I guess if it keeps the meds affordable, it’s worth it. Still… wonder how many people drop out because it’s too much.

Will Neitzer

January 3, 2026 AT 05:22 AMWhile the crossover design is statistically elegant, its practical implementation often overlooks critical physiological variability. For example, circadian rhythms, dietary interactions, and gut microbiome fluctuations can introduce confounding effects even within a single subject - effects that are rarely measured or modeled. The assumption that ‘each person is their own control’ is mathematically sound but biologically oversimplified. Regulatory agencies must evolve beyond fixed confidence intervals and integrate real-world pharmacokinetic dynamics into their evaluation frameworks.

Janice Holmes

January 4, 2026 AT 00:53 AMOkay but imagine being the person who has to sit through FOUR drug periods. Like, you take the generic, wait 14 days, take the brand, wait 14 days, take the generic AGAIN, wait 14 days, take the brand AGAIN. That’s not science - that’s a 56-day drug odyssey with blood draws every 30 minutes. I’d drop out. And the clinic staff? They’re probably just praying for coffee breaks. This system is a glorified torture chamber disguised as innovation.

Elizabeth Alvarez

January 4, 2026 AT 10:03 AMThey say ‘washout period’ but what if they’re lying? What if the ‘five half-lives’ is just a suggestion? What if the lab equipment is calibrated wrong? What if the drug doesn’t fully clear and they just ignore the carryover because the numbers look good? I’ve seen the reports - the sequence-by-treatment interaction p-values are always just above 0.05… too convenient. Someone’s cooking the data. The FDA doesn’t audit these studies. They rubber-stamp them because the pharmaceutical industry funds their conferences. Don’t believe the hype.

James Bowers

January 5, 2026 AT 00:28 AMThe assertion that crossover designs are universally superior is misleading. For drugs with high inter-individual variability - particularly those subject to polymorphic metabolism (e.g., CYP2D6, CYP2C19 substrates) - the assumption of homogeneity across subjects is statistically untenable. The use of replicate designs and RSABE is not merely advantageous; it is methodologically imperative. Failure to adhere to these standards constitutes a violation of ICH E9 guidelines on statistical principles for clinical trials.

Todd Scott

January 5, 2026 AT 01:26 AMFor anyone outside the U.S. or EU - this whole system is a luxury. In countries without the infrastructure for repeated clinic visits, blood sampling, or SAS analysis, parallel designs are still the norm. And yes, they need 80 people instead of 24 - but they’re feasible. The ‘gold standard’ is only gold if you have the resources to polish it. For millions of patients in low-resource settings, the real breakthrough isn’t a fancy crossover - it’s a generic drug that’s affordable, accessible, and approved under any reasonable standard. We shouldn’t romanticize methodology that excludes the people who need it most.