When a generic drug hits the shelf, you might assume it’s just a cheaper copy of the brand-name version. But behind that simple label is a rigorous scientific process to prove it works the same way in your body. That’s where bioequivalence testing comes in. It’s not about whether the pill looks the same - it’s about whether your body absorbs and uses the active ingredient the same way. And there are two main ways to prove it: in vivo and in vitro. One happens inside living people. The other happens in a lab dish. Knowing when each is used can help you understand why some generics are approved faster, cheaper, or with more confidence.

What Bioequivalence Really Means

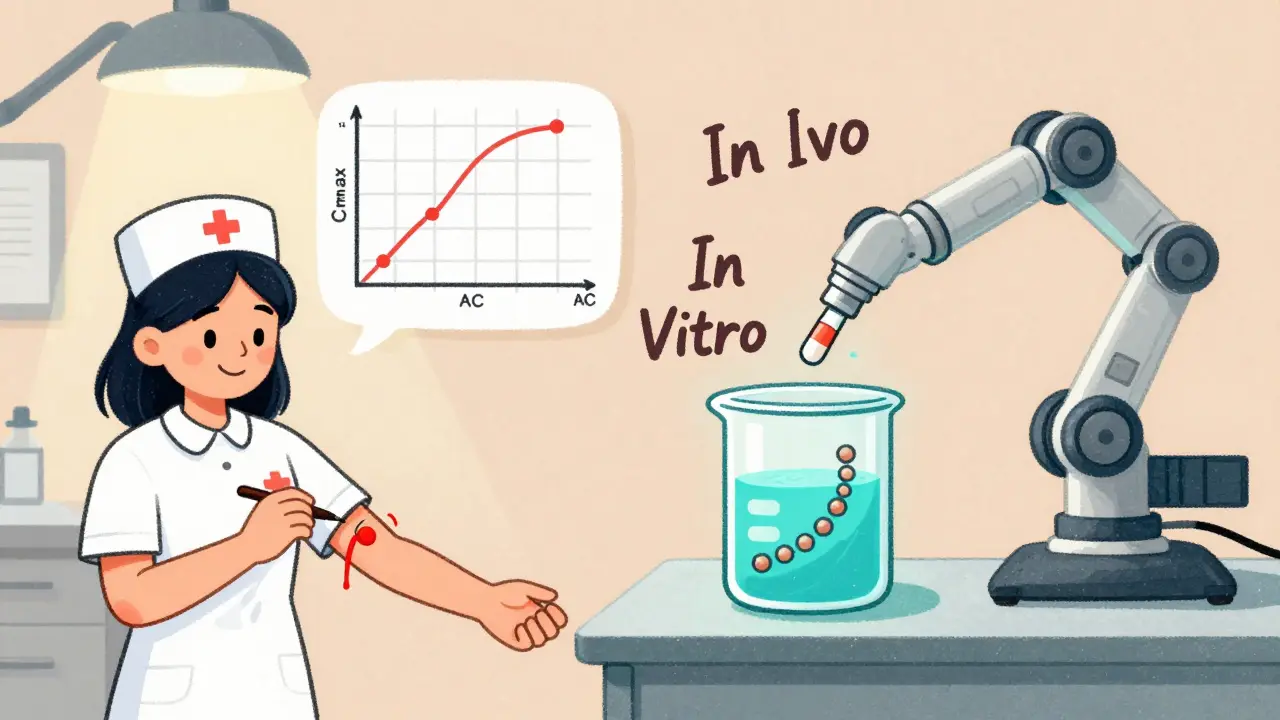

Bioequivalence isn’t about matching ingredients. Two drugs can have the same chemical formula and still behave differently in your body. One might dissolve too slowly. Another might be absorbed unevenly because of how it’s formulated. The goal of bioequivalence testing is to prove that a generic drug delivers the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at the same rate as the original. That’s measured using two key numbers: Cmax (the highest concentration in your blood) and AUC (how much of the drug your body is exposed to over time). The FDA requires that the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of these values between the generic and brand-name drug falls between 80% and 125%. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - like warfarin or levothyroxine - that range tightens to 90%-111.11%. Why? Because even small differences can cause serious side effects or make the drug ineffective. So bioequivalence isn’t just a formality. It’s a safety gate.In Vivo Testing: The Human Body as the Lab

In vivo bioequivalence testing means testing the drug in real people - usually 24 healthy adults. They’re given either the generic or brand-name version, then have their blood drawn repeatedly over 24 to 72 hours. After a washout period, they switch to the other version. This crossover design helps cancel out individual differences in metabolism. This method is the gold standard. It directly measures what matters: how your body handles the drug. It picks up everything - how fast the pill breaks down, how stomach acid affects absorption, whether food changes how much gets into your blood. That’s why it’s still required for most oral solid drugs. About 95% of generic approvals for tablets and capsules rely on in vivo studies. But it’s expensive and slow. A single study can cost between $500,000 and $1 million. It takes 3 to 6 months from start to finish, including screening, dosing, and recovery. You need certified clinical sites, trained staff, and strict compliance with FDA regulations like 21 CFR Part 11 for electronic records. There’s also the ethical layer - exposing healthy volunteers to drugs, even if they’re approved. Still, for some drugs, there’s no shortcut. If a drug has food effects, nonlinear metabolism, or is absorbed only in a specific part of the gut, in vivo testing is the only way to see how the product really performs.In Vitro Testing: The Lab’s Role in Proving Equivalence

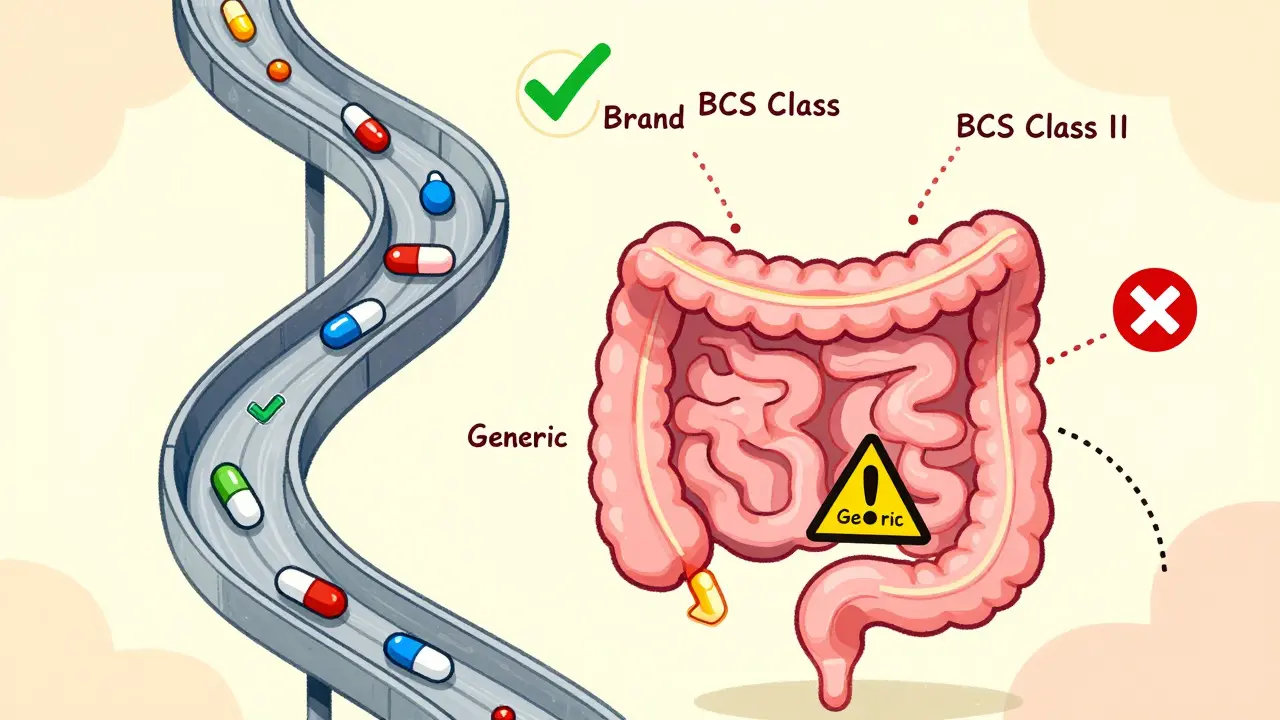

In vitro testing skips the human body entirely. Instead, scientists use machines and lab techniques to measure physical and chemical properties. The most common method is dissolution testing: placing the pill in a fluid that mimics stomach or intestinal conditions and measuring how quickly the drug dissolves. Other methods include checking particle size, droplet distribution (for inhalers), or how much drug comes out per spray. These tests are precise. Dissolution results often have a coefficient of variation under 5%, compared to 10-20% in human studies. That means less noise, more control. And they’re fast. A well-developed in vitro method can be ready in 2-4 weeks, costing $50,000-$150,000 - a fraction of the price of a human study. The FDA accepts in vitro methods for certain products. For example, if a drug is BCS Class I - meaning it’s highly soluble and highly permeable - it’s very likely to be absorbed the same way no matter how it’s formulated. In 2021, the FDA granted biowaivers (approval without in vivo testing) for 78% of BCS Class I generic applications. That’s why drugs like ibuprofen or metformin often skip human trials. In vitro testing is also essential for complex delivery systems. Think inhalers, nasal sprays, or topical creams. You can’t easily measure drug levels in the lungs or skin through blood tests. But you can measure how many microns the particles are, how evenly they’re distributed, or how much drug is delivered per puff. The FDA now accepts in vitro data alone for some inhalers and nasal sprays - like Teva’s generic budesonide nasal spray approved in 2022.

When In Vitro Works - And When It Doesn’t

In vitro testing shines in four clear cases:- BCS Class I drugs - high solubility, high permeability. These are the low-hanging fruit for biowaivers.

- Locally acting products - like nasal sprays for allergies or topical creams for eczema. If the drug doesn’t enter the bloodstream, why measure blood levels?

- Complex delivery systems - inhalers, patches, suspensions. In vivo testing is often impractical or unreliable.

- Validated IVIVC models - when a lab test has been proven to predict human absorption with high accuracy (r² > 0.95). This has been done successfully for modified-release theophylline and some extended-release tablets.

- Narrow therapeutic index drugs - small differences matter. In vitro can’t capture subtle changes in absorption that could lead to toxicity or treatment failure.

- Drugs with food effects - if a pill absorbs better with a fatty meal, in vitro tests in water won’t show that.

- BCS Class III drugs - highly soluble but poorly permeable. In vitro dissolution may look perfect, but the drug still won’t cross the gut wall. Studies show in vitro predicts in vivo performance for only 65% of these drugs.

- Drugs with complex absorption patterns - like those absorbed only in the small intestine or affected by gut enzymes. The human body is messy. Lab conditions are clean. That gap matters.

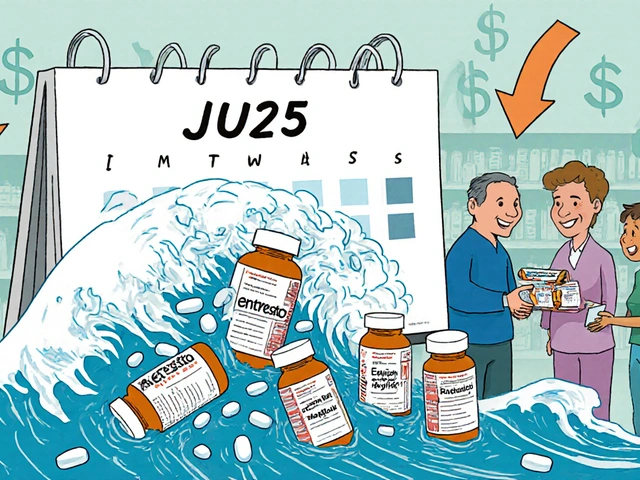

Regulatory Trends: The Shift Toward In Vitro

The regulatory world is moving. The FDA’s 2020-2025 Strategic Plan pushes for more in vitro methods. The European Medicines Agency approved 214 biowaivers based on in vitro data in 2022 - up 27% from 2020. Japan and the EU now align with the U.S. on accepting in vitro testing for BCS Class I drugs. The 2023 FDA draft guidance on nasal sprays and inhalers says in vitro testing alone can be enough - if done right. The agency is also embracing in silico tools - computer models that simulate how a drug behaves in the body. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling is now accepted for some extended-release products. Industry is responding. A Teva scientist reported saving $1.2 million and 8 months on a BCS Class I product by using in vitro testing. But it wasn’t easy. It took 3 months to develop a method that met FDA standards. The equipment - like USP Apparatus 4 flow-through cells - costs $85,000-$120,000. And not every company has the expertise. Still, the trend is clear: in vitro is becoming the first choice where it’s scientifically valid. The FDA’s GDUFA IV plan (2023-2027) commits to issuing two new guidances on in vitro testing for complex products by December 2025.

Real-World Risks and Lessons

There’s a cautionary tale here. A generic topical antifungal was approved based on in vitro data. Months later, patients reported the cream wasn’t working as well. A post-marketing in vivo study found differences in skin absorption. The company had to spend $850,000 and delay market expansion by 11 months. That’s the risk of over-relying on in vitro. Just because a pill dissolves fast in a beaker doesn’t mean it’ll work the same on a person’s skin or in a patient’s gut. In vitro is powerful, but it’s a proxy - not a perfect mirror. Experts like Dr. Gordon Amidon (who helped create the BCS system) say in vitro methods can be better than human studies for simple drugs because they measure product performance directly. But Dr. Lawrence Lesko, former FDA pharmacology director, warns: “In vitro methods can’t replicate the chaos of the human GI tract.” The takeaway? Use the right tool for the job. For a simple, well-understood drug, in vitro is faster, cheaper, and just as reliable. For high-risk, complex, or poorly understood drugs, in vivo remains essential.What This Means for You

If you’re a patient, you don’t need to memorize BCS classes or dissolution profiles. But you should know this: not all generics are approved the same way. A generic ibuprofen was likely approved without human testing - and that’s safe. A generic blood thinner? That one almost certainly went through human trials - and for good reason. If you’re in pharma - whether you’re a scientist, regulator, or investor - the message is clear: invest in in vitro methods where they work. Build the expertise. Validate the models. But don’t abandon in vivo testing when the stakes are high. The future of bioequivalence isn’t in vitro or in vivo. It’s in vitro and in vivo - used together, intelligently. For most drugs, in vitro will lead. For the most critical ones, in vivo will still be the final gatekeeper.What’s the difference between in vivo and in vitro bioequivalence testing?

In vivo testing measures how a drug behaves inside the human body, typically using blood samples from volunteers to track absorption. In vitro testing happens in a lab, using physical and chemical methods like dissolution testing to measure how the drug releases from its formulation. In vivo reflects real-world performance; in vitro measures product characteristics that are expected to predict that performance.

When can a generic drug be approved without human testing?

A generic drug can be approved without human (in vivo) testing if it meets specific criteria: it’s a BCS Class I drug (highly soluble and highly permeable), it’s a locally acting product like a nasal spray or topical cream, or if a validated in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) model exists. The FDA grants biowaivers for these cases, saving time and cost while maintaining safety.

Why is in vivo testing still required for some drugs?

In vivo testing is required for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (like warfarin or levothyroxine), those affected by food, drugs with nonlinear metabolism, or when the site of action isn’t systemic. These factors are hard to predict in a lab. Human studies are the only way to ensure the drug performs safely and effectively in real patients.

How accurate is in vitro testing compared to in vivo?

In vitro testing is highly accurate for BCS Class I drugs - predicting in vivo performance in 92% of cases. For BCS Class III drugs (high solubility, low permeability), accuracy drops to 65%. It’s also very reliable for inhalers and nasal sprays when paired with particle size and dose delivery tests. But it can’t replicate the full complexity of human digestion, absorption, and metabolism.

Is in vitro testing cheaper than in vivo?

Yes, significantly. In vitro testing typically costs $50,000-$150,000 and takes 2-4 weeks. In vivo studies cost $500,000-$1 million and take 3-6 months. That’s why companies push for in vitro biowaivers - especially for simple, well-understood drugs.

What’s the future of bioequivalence testing?

The future is hybrid. In vitro methods will become the default for most generic drugs, especially with advances in modeling like PBPK. In vivo testing will be reserved for high-risk cases: narrow therapeutic index drugs, complex delivery systems without validated models, and products where human response is unpredictable. The FDA aims to issue new guidances on in vitro testing for complex products by 2025, signaling a major shift toward science-based, efficient approvals.

Lori Anne Franklin

December 25, 2025 AT 16:12 PMI always thought generics were just cheap knockoffs, but this broke it down so nicely. Like, ibuprofen? Totally fine without human trials. Blood thinners? Yeah, better test it on people. Makes sense now.

Bryan Woods

December 26, 2025 AT 06:23 AMThe distinction between BCS Class I and III is critical. Many regulatory bodies still underappreciate the limitations of in vitro methods for poorly permeable compounds. This post accurately reflects the scientific consensus.

Ryan Cheng

December 27, 2025 AT 14:39 PMBig props to the author for making this super clear. I work in pharma and even I get lost in the jargon sometimes. The part about dissolution testing being cheaper and faster? Yes. The part about why we still need human trials for warfarin? Also yes. Keep this stuff coming.

wendy parrales fong

December 27, 2025 AT 17:26 PMIt's kind of beautiful how science finds ways to be both precise and practical. Like, why test on humans if a pill dissolves the same in a beaker? But then again, our bodies are wild and messy. Maybe the real answer is to use both. Just... gently.

Sarah Holmes

December 29, 2025 AT 08:27 AMThis is a textbook example of regulatory capture disguised as innovation. In vitro testing is cheaper for corporations, not safer for patients. The FDA's shift toward biowaivers is a betrayal of public health. We are trading certainty for profit, and the consequences will be measured in overdoses and treatment failures.

christian ebongue

December 30, 2025 AT 15:03 PMbcg class i? lol. you mean bcs. typo. but yeah, ibuprofen generics are fine. no one cares if it dissolves in 12 vs 14 mins. warfarin? yeah, test it on humans. duh.

jesse chen

December 31, 2025 AT 09:04 AMI really appreciate how thorough this is... especially the part about nasal sprays... and the fact that in vitro can be more consistent... and the cost difference... and the FDA's push for efficiency... and the risks of skipping human trials... and the IVIVC models... and the Teva example...

Joanne Smith

December 31, 2025 AT 19:46 PMLet’s be real - in vitro testing is the corporate love letter to ‘move fast and break nothing.’ But when a topical antifungal fails because the cream’s texture changed slightly and now it won’t penetrate? That’s not science. That’s negligence dressed up as innovation. I’ve seen it happen. The lab says ‘perfect dissolution.’ The patient says ‘it’s useless.’ Guess who pays?

Prasanthi Kontemukkala

January 1, 2026 AT 17:27 PMThis is such a balanced view. I'm from India, and we have so many generics here - some amazing, some questionable. This helps me understand why. In vitro for simple drugs, in vivo for the high-risk ones. It’s not about cutting corners. It’s about using the right tool. Thank you.

Alex Ragen

January 3, 2026 AT 00:32 AMAh, yes. The great in vitro delusion. You think you've tamed the chaos of human physiology with a dissolution apparatus? How quaint. The GI tract is not a beaker. The liver is not a spectrometer. The FDA's embrace of this is not progress - it's the surrender of science to the tyranny of cost-efficiency. The BCS system? A beautiful lie for the corporate age.

Jeanette Jeffrey

January 4, 2026 AT 00:24 AMSo you're telling me we're letting companies skip human trials for drugs people take daily... just because they're 'soluble'? That's not science. That's gambling with lives. And now we're calling it 'innovation'? Please. This is how you get another Vioxx. And someone will die. And then they'll say 'we didn't know.' We did know.

Shreyash Gupta

January 5, 2026 AT 16:45 PMin vitro = good for big pharma 😎 in vivo = good for patients 🤕 so why are we doing in vitro? 💸 someone please explain... 🤔

Ellie Stretshberry

January 5, 2026 AT 21:20 PMI read this at 2am and it actually made sense. I'm not a scientist but I take meds. I just want to know if the cheap one will work. This helped. Also the part about food affecting absorption? That's wild. I always thought it was just about stomach upset

Zina Constantin

January 7, 2026 AT 09:29 AMThis is exactly the kind of clarity we need in public health discourse. The fusion of science and pragmatism here is inspiring. In vitro isn't the enemy - ignorance is. And this post? It's a gift to anyone trying to navigate the noise.

Dan Alatepe

January 7, 2026 AT 09:50 AMBro... imagine spending $1 million to test a pill on 24 people... and then someone says 'wait, what if we just shake it in water?' 😳 $50k? 2 weeks? That's like comparing a Ferrari to a bicycle... but the bicycle gets you to the same place... sometimes 🤯 I'm just saying... maybe we don't need the Ferrari for every road